This November 1895 encounter left a powerful mark on Herzl, who at the time was under intense pressure to abort his plans to publish “The Jewish State” and abandon his dreams. Goldsmid, who was the regional commander in Cardiff, Wales, hosted Herzl in his home for dinner. “I am Daniel Deronda,” he told Herzl in an emotional late-night confession, referring to George Eliot’s novel about a man who discovers his Jewish roots, converts back to Judaism and is set to fulfil the dream of the return of the Jews to their land. His conversion to Judaism was not a rejection of Christianity, but rather a return to the people he felt a part of. Goldsmid was a Victorian-era British gentleman, an alumnus of Sandhurst Military Academy. The astonishing thing was the manner in which Goldsmid connected back to Judaism – not through the Jewish religion itself as much as through his strong sense of Jewish nationalism. Raised as a Christian in a British military family in India, Goldsmid discovered his Jewish ancestry when he was a teenager, and eventually converted to Judaism. Goldsmid was a different type of assimilated Jew. He was a cosmopolitan Frenchman, living a life of luxury in Paris in the 16th Arrondissement near Trocadero Square, dwelling in the Parisian society of the Belle-Epoque. When the French lost that territory to Germany in the 1870 war, his family opted against staying in their home under German occupation, and instead chose to become “refugees,” eventually moving to Paris.ĭreyfus rejected the idea of Jewish nationalism, just as he rejected Jewish religiosity. Like many in the French military at the time, Dreyfus was from Alsace.

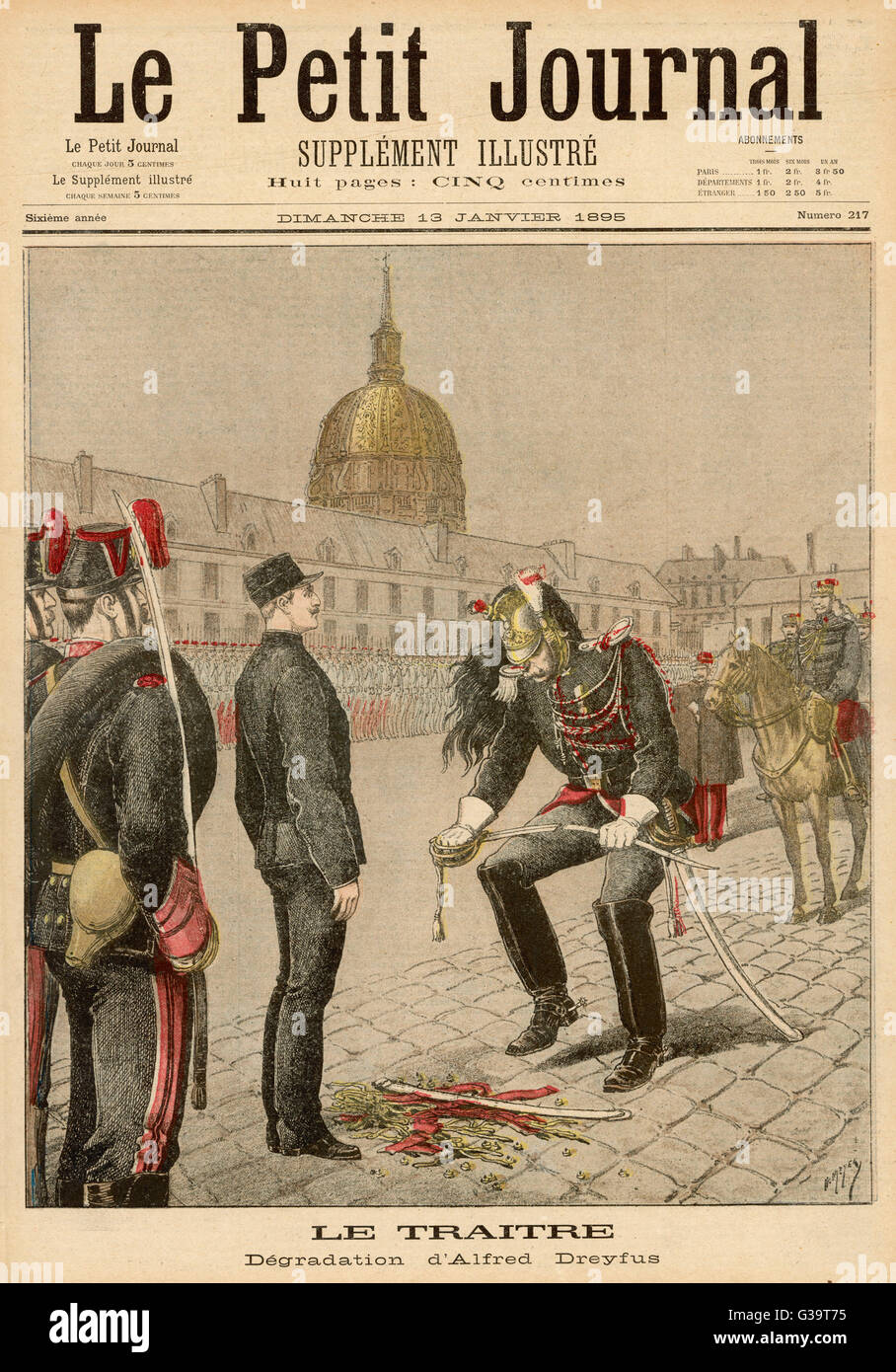

In what was to become one of the most horrific acts of state-sponsored antisemitism spanning multiple levels of the French government, military, press, the French Catholic church and Parisian society, the Jewish officer was falsely accused of treason against France.įrance’s dismissal of Dreyfus’s patriotism came in spite of his demonstration of passionate loyalty to France. Indeed, the French rejected Dreyfus’s patriotism as they rejected the Huguenot Protestants centuries earlier. “It is useless, therefore, for us to be loyal patriots, as were the Huguenots who were forced to emigrate.” “In countries where we have lived for centuries we are still cried down as strangers,” he said. Herzl noted how such patriotism was utterly rejected by Europeans. Historian Michael Marrus argues that patriotism was the cornerstone of newly emancipated European Judaism and that it received encouragement from the highest Jewish religious officials, such as the Grand Rabbi of France. Herzl addressed such Jewish patriotism in his writings: “In vain are we loyal patriots, our loyalty in some places running to extremes in vain do we make the same sacrifices of life and property as our fellow-citizens in vain do we strive to increase the fame of our native land in science and art, or her wealth by trade and commerce.” Such patriotism was rewarded in 1857 by Austrian Kaiser Franz Joseph, who gave Herzl’s ancestors permission to purchase land throughout the empire. Herzl himself came from a family of patriots, who demonstrated strong multi-generational loyalty to the Austrian monarch, including by helping the Austrian war effort against the Turks. They were among the highest-ranking Jews ever to serve in a European army. Dreyfus rejected it, Goldsmid embraced it.īoth Dreyfus and Goldsmid were devout patriots, serving their respective countries. The two Jewish officers represented opposite bookends of assimilated European Jews’ attitudes toward Jewish nationalism.

A few months after their dramatic meeting, Herzl unveiled his Zionist philosophy to the world, and in February 1896 published “The Jewish State.”

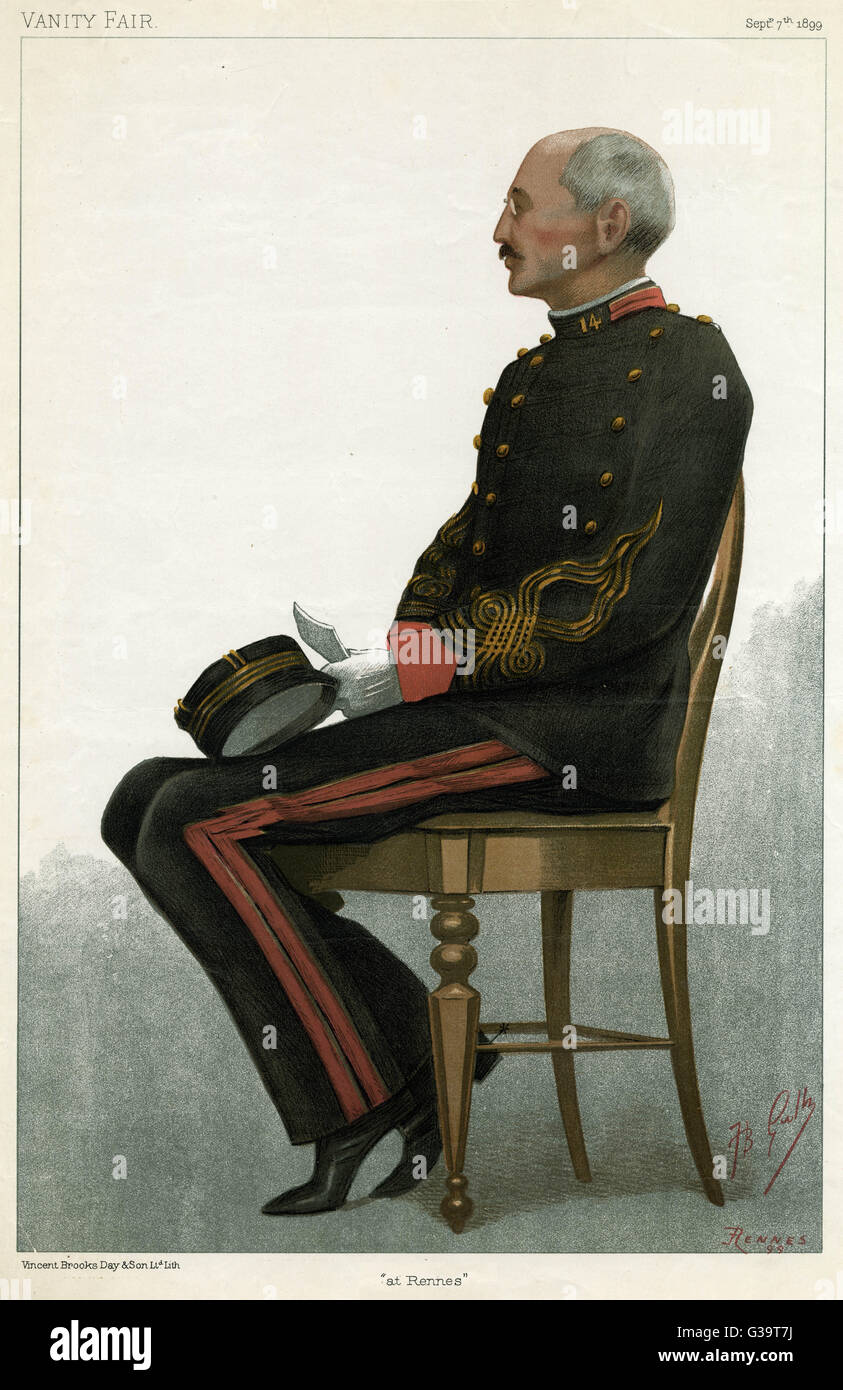

Albert Goldsmid, a British Jewish officer whom Herzl met about a year later in November 1895.

#Alfred dreyfus received support from who free

Herzl never met Dreyfus, but carefully watched him during the trial, which he covered as the Paris correspondent of the Viennese newspaper, Neue Freie Presse (New Free Press.) Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish officer who in December 1894 was convicted of treason. Two assimilated Jews who were high-ranking European officers had a profound effect on Theodor Herzl, in the early stages of Zionism as his ideas were fermenting in his mind.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)